Dreaming of a Beach House

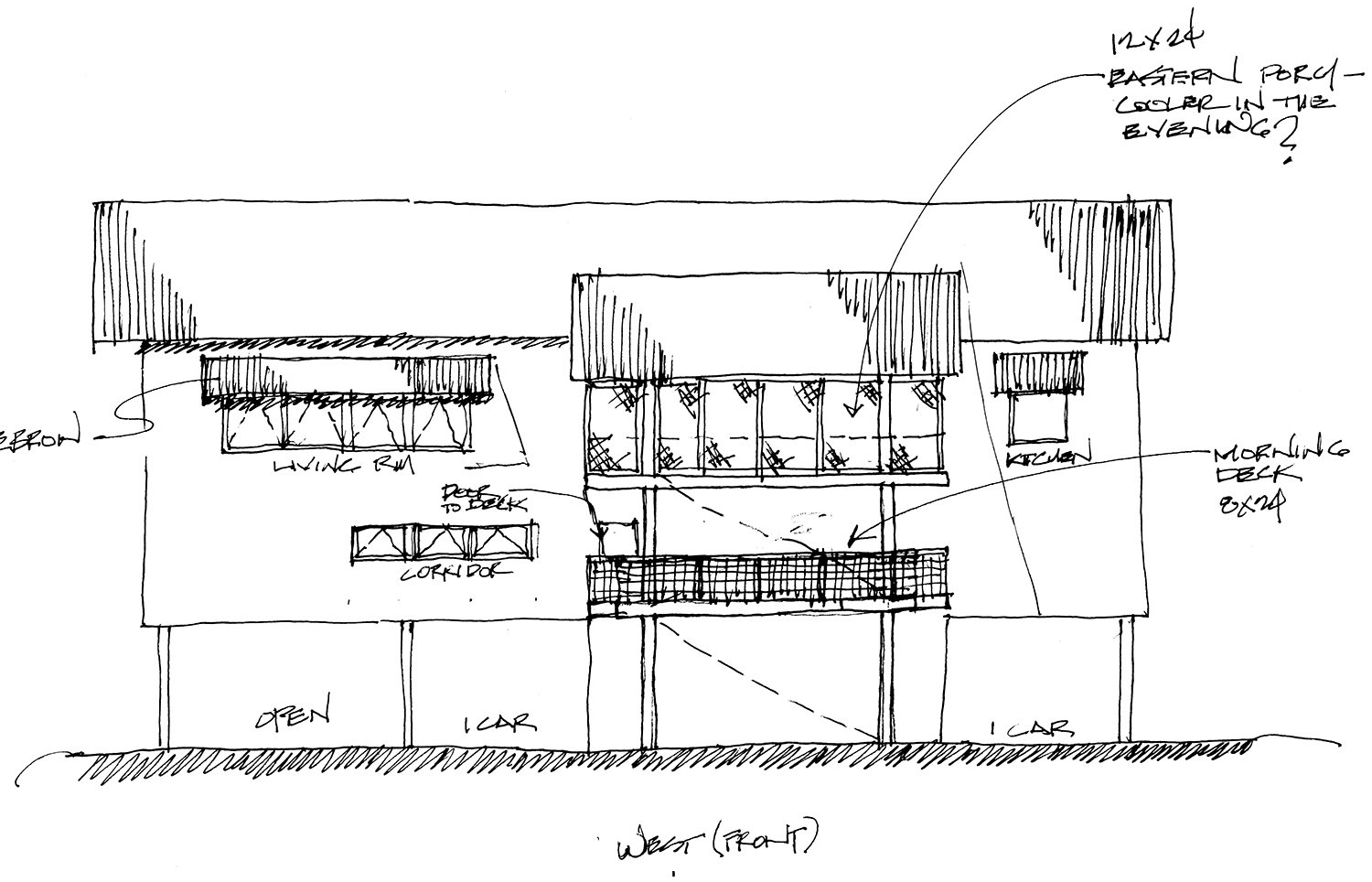

Early elevation sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

When did Le Corbusier ever worry about site grades? He was an artiste, to be sure. Though he didn’t care too much for less cared-for parts of Paris, also known as affordable housing. His vision for the modern city seemed to take up with the arrival of bulldozers shortly before the remake of 1984 began. There’s a remarkable similarity to Coop City in greater New York City I used to pass driving to Connecticut.

Model of the Plan Voisin for Paris by Le Corbusier—photo by SiefkinDR

When the subject was last broached, the fictitious beach house site, sitting well away from the water, had been studied from earth and drone both. Fictitious because it’s still an undeveloped tract. Yes, if one stood on a twenty foot ladder toward the rear of the site, Currituck Sound might be visible, and still further off in the east, across a cover of trees and houses, the Atlantic Ocean. So, the living spaces needed to be on top—inverted houses aren’t unusual on the Outer Banks.

We faced the opposite problem at home—the sites all slope down toward the lake. Ironically, the living spaces on our house were on the upper level as well, thus he design challenge was how to avoid going down fifteen feet to a lower level front door, then back up again to reach the living room and kitchen. The photo by Eric Taylor explains the solution.

Lake House—photo by Eric Taylor, ©2013

But the beach site’s grade is another kind of challenge. Any builder will tell you a dozer can quickly level hilltops and clear the trees, however if the crest is where you want to build, grading it level is working at cross purposes. The site is on a fairly constant five to six percent grade, rising from the street, so if you apply the typical squarish house shape, the grade at the front (facing the view) would be five or more feet below the rear. Coupled with the expectation of founding it on 8x8 wood piers in the Outer Banks’ tradition, setting it at the higher rear elevation implies an impossibly tall ground level requiring ginormous wood members, technically speaking.

Keeping to the narrowest width, stretching the house across the site, became a primary influence on the design, keeping as much as possible to a one room width. With the added benefits of more rooms with views and great cross ventilation. The early studies were included in two previous blogs, Notes on a Beach House and Design Notes #2 if you missed them.

Of the four main options, the one that I was attracted to most was dubbed the “Bar House” for the length of it, with a straight run stair running parallel along the front (west) side, and decks/porches on both of the occupied levels. Though the extent of the decks concerned me—they’re great for shading the interior, but are expensive to maintain in a salt-laden environment.

The largest drawback to locating the living spaces on top—other than schlepping groceries two floors—is the requisite deck and/or screen porch at that level needs to be supported by the floor decks below. Either that or sky hooks. One carpenter I worked with loved telling the new kid to ‘go fetch some sky hooks from Lowes.’

Being as high above sea level as the site is, I considered not raising it up the entire full story from grade, but the zoning-required 4-5 parking spaces would take too much of the front yard. Aside from the aesthetics, it would also increase the amount of impervious area on the site. So that meant going the full story.

I began to sketch variations.

The straight run stair seemed like a win-win. It could be a feature visible on the exterior, as well as the interior; it would expand the volume of the public rooms on top overlooking the stair. In the Bar House, the kitchen overlooks the stair and hall, the living/dining area facing west, south and east, and a bedroom at the north end.

Somewhere along the line, my client insisted she wanted a screen porch for summer evening dinners. Nice thought. Mixing insects with one’s salad may add fresh protein, however…

Bar House—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

The first attempt at a western elevation perched a screen porch on two-story columns off the kitchen and left the living room exposed to the late afternoon sun. Other than the structural contortions it would require, it was too reminiscent of a barn on stilts.

Early elevation—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

The second elevation sketch had something going for it, though despite the roof ‘brow’ over the living room windows, it would require sunglasses come sunset. And it retained that top heavy barn look—maybe finish it like an oversized Tahitian villa Gauguin might have enjoyed?

Early elevation—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

Or an oversized dormer to balance the deck/porch assembly? It was being driven home that the western orientation was not without aesthetic issues.

Early elevation—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

When beginning a design problem, you’d best come with a natural optimism, or consider finding another trade. It isn’t until you’ve wrestled with it for a while that reality sets in and the real search begins.

So, cover the entire western face with deck and porch? Shaggy dog time. And if the dinner porch faces west, it will retain the entire afternoon heat right up until bedtime. The dinner porch needed to move to the eastern side, or it would never be used. Likewise, in the winter months when folks like to read outside on a deck, much of the sun’s warmth would be blocked by a porch roof.

Early elevation—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

To say a word about the eastern view—we have one—at least until the lot behind us is developed. The site’s rear reaches the top of a crest and drops away again on the lot beyond. So depending on how much work whoever develops the property to the rear does, we still might be a story taller, i.e. with a view across the island. It could work.

Wild Hair

At the same time as the ‘Bar’ plans were being worked on, something was nagging at me. I wanted to find a way to split the single object into several. I’ve often sought to play one mass against another. An early modernist’s house for himself has stayed with me—nestled in rocks by a New England shore, with the courtyard partially enclosed by separate building elements. I can’t find a reference, but believe it was Marcel Breuer’s work.

Also, the image of Alvar Aalto’s assemblages, one being his town hall for Säynätsalo, Finland.

We once had a local version of early modern, Bauhaus style, sitting at the edge of Lake Barcroft, the main house tied by a flat roof to an otherwise free-standing studio. Glass and framed panel walls reminding of de Stijl. It was demo’d down to its foundations several years ago—too small? —not grand enough? —now replaced by an arm waving awkwardness with a multi-colored light show Pink Floyd would be proud of.

Walter Gropius’s Hagerty House as featured in Dwell was built in 1938. Architects have been chasing views of the ocean since forever.

Brian MacKay-Lyons, Nova Scotia’s best know architect, has done well with the idea. Smith Residence.

Design time is free when it’s your own. The problem that stopped me was the open deck that works dramatically well in New England and Nova Scotia, becomes problematic on the Outer Banks. And the extent of exterior walls would drive up the price tag. A single level bridge is one thing, but with stairs in one or the other element—what if the stair becomes the bridge? There’s a thought…

So sighing, I returned to the Bar House, trying on decks, porches, stairs, etc.

Early plan—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

Somewhere in the throes of sketching—throwing bumwad at the wall, my client voiced opposition to the stair and hallway being between the kitchen and the view, despite explanations that she’d be looking over and past both.

A few iterations later, a straight run stair was laid up beside the living room, and the corridor flipped to the rear, then it went away again. Keeping the first and second floor corridors on the east face, and the stair/elevator on the west meant a cross corridor to connect them on the first floor, screwing up that layout. Bumwad was flying hither and yon.

Early plan—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

Stumbling on, the straight run stair was replaced by a double-back stair set perpendicular to the ‘bar’ and the first inkling of a decent elevation.

Early plan—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

Early elevation—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021

Waiting to receive a scalable site survey, I sketched something resembling what I’d been thinking about. Now if I can get Revit to make a decent roof form over this beast, I’ll be able to move on to pulling together the working drawings.

Site plan—sketch by William E. Evans, ©2021