Summer Home

Early entrance perspective from bridge—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

This is the somewhat true story of how a house built in 1952 became our family home fifty years later. Back before electricity, they called them summer homes, and the name stuck. This particular house had been built before AC was more than a window shaker per room.

It had been sitting on the market for several months when I and the dogs tramped by. I like to tell the story—and everyone yawns, ‘oh, dear, look at the time.’ But it begins with walking two huskies, as all worthwhile stories should.

I know nothing about whose house it was originally, who built it, nothing. They’ve gone into history. We are possibly only the third maybe fourth owners. For some time it has struck me our homes outlive us, we but tenants, no matter how much we like to imagine them as reflections of ourselves—like I do.

The owners previous to us had used it a few years for a summer home. He, a thoracic surgeon needing a tax write-off, and she his mate whose household jobs were how most women coped not so long ago. Never met the great man until closing, but Biddy came across as a down to earth sort when, with the house under contract, we sat on the outside deck to talk. My impression was she would miss the place.

She said they’d wanted to add enough bedroom space for their family of several teenage boys, expecting the addition to be in the widest part of the site—by the road—and at some point gave up in frustration. Don’t recall if they were working with an architect, but in any case, they’d just bought a house on the far side of the lake already sized for an army, putting this one up for sale, eh, voila!

Mojo. Maddie and I had taken an extra long hike from Stoneybrae, down Waterway, across the Women’s Club pedestrian bridge to Lakeview running the south side of the lake, and from there to the far end closest to Columbia Pike, a couple hours involving a great deal of sniffing and peeing. We had done it a handful of times before, but this time, the ‘for sale’ sign surprised me, for no other reason than when we’d walked that way before, I’d seen no one living there, nary a car parked outside.

Lake Barcroft has a remarkably large number of the elderly who chose to retire in place. This was abundantly clear from when we first found the community. Seeing the house so empty, I’d assumed this was another case where the place had outlived the owner. It’s poignant seeing lonely old folks holed up inside by themselves. I’m like the dog who knows no good will come of it.

Existing property from the road—photo by William E. Evans, © 2004

You can’t see the carport for the large holly bush.

Descending from the road—photo by William E. Evans, © 2004

Note the dip in the foreground railing, resulting from an attack of an angry tree limb. The tree itself, a majestic red oak, shaded the holly bush before meeting its demise, taking the small carport cupola (no loss) with it. We’d already been in the place for several years with still no renovation started. Why rush?

Not so many photos of the Lakeview house before we started the work. Somewhere I have shots taken from standing in the middle of the cove that first winter when the ice was thick enough to walk on. Hasn’t been that solid since.

…

From the road, it appeared to be a cottage barely joined to terra firma—sitting so far into the lake. Vaguely New Orleans’ French Quarter with a smallish wrought iron balcony over the front door where Al Hirt might could pose solo with trumpet. Wood shingle roof, 10-inch vertical board siding—the real stuff—and painted yellow, god help me, sitting atop the lower level masonry also painted yellow.

I married a real estate connoisseur without fully grasping the fact; it seemed our tastes were broadly aligned. Returning from the dog walk, when I told D the house was on the market, the mere suggestion convinced her to tour it. Before Covid shut us all indoors, the Barcroft house tour—a Women’s Club charity fundraiser—was an annual springtime event we rarely missed.

Though the greatest curiosity was how one found the entrance to this place, descending exterior stairs beside the carport to cross the lawn—set sideways—before arriving at the front door tucked under the balcony. Then ascending again to the main living level on the second floor. It was a side house to fit the site, like the more famous ones in Charleston. But the living room faced the water—with windows clouded from early insulated glass panes.

Expecting to find cherubs on the mantel, we entered the living room with vertical blue and white striped wallpaper—beachy like you see in photos of Bermuda homes. But neither of us took notice—for the view from the living room. Across a somewhat narrow cove, toward one of the longer views on the lake, all the way across to John Podesta’s art museum, which we once toured. His girlfriend was a docent for the house that year. Some of the ‘art’ was, ah, well, not so artful.

Admittedly, it was the view that held us captive. We were willing to overlook the quirkiness of the house layout for the view. A more critical eye might have been turned off by the awkward shape of the site. But no site is impossible as the architect said to himself.

In my mind, it was a ridiculous gamble that D and I were betting on, especially since we hadn’t been making plans to buy another house. The living-dining-kitchen space was a healthy size—for a townhouse. The kitchen in particular. The kitchen might have been a galley kitchen found in 18th century townhouses in DC. We’d be giving up our recently renovated kitchen.

But look at the view!

Lake Barcroft History

Lake Barcroft is a narrow finger lake following the contours of the two tributaries feeding it. With only 250 lakefront houses, they often never reach the open market—someone knowing someone learns of a house and makes an offer before it’s listed. Back in the 1950s, the lake and the land had been sold off by the Alexandria Water Company. No longer furnishing water to the city of Alexandria. the lots surrounding Lake Barcroft were being sold cheap.

We’d heard the stories, how the original development was so far in the outskirts of Arlington-Alexandria that it was considered hinterland best suitable for affordable summer homes. Arlington’s influence is noticeable with the small, red brick houses scattered throughout the community. Later in the 60s and 70s ranch style homes came into fashion. But with a few exceptions, the houses have continued to be less aggrandized than in McLean and Great Falls. Partly with smaller size lots, but also due to being less ‘discovered.’

The general area was named for Dr. John W. Barcroft, who built a grain mill in the late 1840s near the present-day dam, evidence that the flow and fall were generous enough to power the mill’s wheel. What historic artifacts from the mill, if they exist, likely lie under sixty-plus feet of water.

The cyclopean dam was built in 1913—cyclopean referring to its gravity structural type, [1] not that the Cyclopes had lifted the stones in place—capturing the flows from Holmes Run and Tripps Run.

[1] “A gravity dam in which the mass masonry consists primarily of large one-man or derrick stone embedded in concrete.” from Stanford University NPDP Dam Dictionary

“The result was a dam 400 feet wide with the spillway at the top 205 feet above mean sea level and 63 feet above the stream bed. Behind this dam there formed a lake of 115 acres and over five miles of shoreline. When full it held nearly 620,000,000 gallons and had an average daily runoff of about 10,000,000 gallons. In 1942 gates were installed at the top of the dam to raise the spillway level five feet. This increased the size of the reservoir to 135 acres and the capacity to about 800,000,000 gallons.

Rumor has it there’s a house designed, or at least influenced by, Walter Gropius, one of early Modern’s founding lights. The recent WP article below suggests Gropius influenced the layout of the community as a whole, presumably its winding roads, a clear disinterest in regrading the hills, and perhaps the modest lot sizes.

“Lake Barcroft was founded [sic] in 1950 by a partnership led by Col. Joseph V. Barger, who purchased a reservoir from the Alexandria Water Works. Barger approached Walter Gropius, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Architecture and Design and originator of the Bauhaus style, [actually, he was an original teacher at the Bauhaus] to help develop the neighborhood. About 25 to 30 percent of the houses are mid-century modern, with a handful by renowned architect Charles Goodman, said Lisa DuBois, a real estate agent and resident.”

“Notable past [Barcroft] residents include Pierre Salinger, Ramsey Clark and Bob Dole. Former U.S. senator Jim Webb (D-Va.) still lives there, as does 92-year-old Cecilia ‘Cissy’ Marshall, the widow of Justice Thurgood Marshall.”

from Washington Post In Fairfax County, a lakeside community gets its hooks into residents by Connie Dufner, 2021

And just up the street from us, two Charles Goodman houses are up for sale—Goodman is largely credited with how Hollin Hills in Hybla Valley was later developed—now a National Historic District. Goodman was one of only a handful of Washington area architects to pursue Modern design—the so-called the mid-century Modern we both admire.

First Impressions

The house in question was built in 1952, when I was three. I don’t recall it under construction, mainly because at the time I lived two states south of Virginia—in a toddler’s state of mind. Originally three small bedrooms upstairs, two bathrooms, and an odd fourth sunroom downstairs at the far end away from the lake and adjacent to a jumble of interior bathroom and utility space jammed against the basement wall. Up a steep staircase only a mountaineer could love was a low-ceilinged attic, since finished.

It wasn’t until crawling into the unfinished attic and opening walls I began to suss out how it was constructed— and discovered the original house didn’t even have drywall ceilings—evidenced by the white painted wood joists and deck I spied with a flashlight. Only the narrow family room downstairs retained a bit of the look, with its exposed ceiling joists of rough-dressed lumber (2 ½ x 12 ½). Somewhere in its life, the family room’s interior walls became brick, matching the exterior.

Layla and the sample ‘S’ for Signature Theatre’s marque. She’s not impressed.

It took multiple physical examinations to determine the entire house had been built with rough-dressed pine lumber, with beam sizes no longer available. Nary a piece of nominally sized lumber until we began the addition. Somewhere someone could be still building with rough-sawn lumber; we had found a home old enough to be built with it, and I wasn’t going to demolish any more than necessary.

Seemed very little alteration had been done over the years before we moved in. Two bedrooms had been merged into a single master bedroom with a larger than normal bathroom and walk-in closet—done in the 1980s. And a curious pair of French doors opening to the yard in the lower level sunroom, curious because they’d been since permanently closed, though still with hinges visible on the exterior.

Elder azaleas and rhododendrons were flourishing under a deciduous tree canopy shading the entire site. The bushes had likely been planted shortly after the house was built, being ten feet and taller. The boxwood hedge leading to the front door was easily as old.

Early Concepts

A poem I wrote to Ryan, who’d never seen the interior, describes the house as we had found it: French Quarter Tour. Ryan and I had only walked the outside, before we’d closed on the house, and before he headed to Virginia Tech. We closed in August, and he was gone from our lives by that October. Love in Winter—Missing Ryan covers the time of the following winter of 2002-2003, when, if I wasn’t writing, I was holed up in the attic sketching to distract myself.

Somewhere buried in the attic are the sketches I drew over that winter. Being that I’d never designed a house for us to completion, coupled with being insane with grief, I went from one extreme to another, much indifferent to whether anything might come of it.

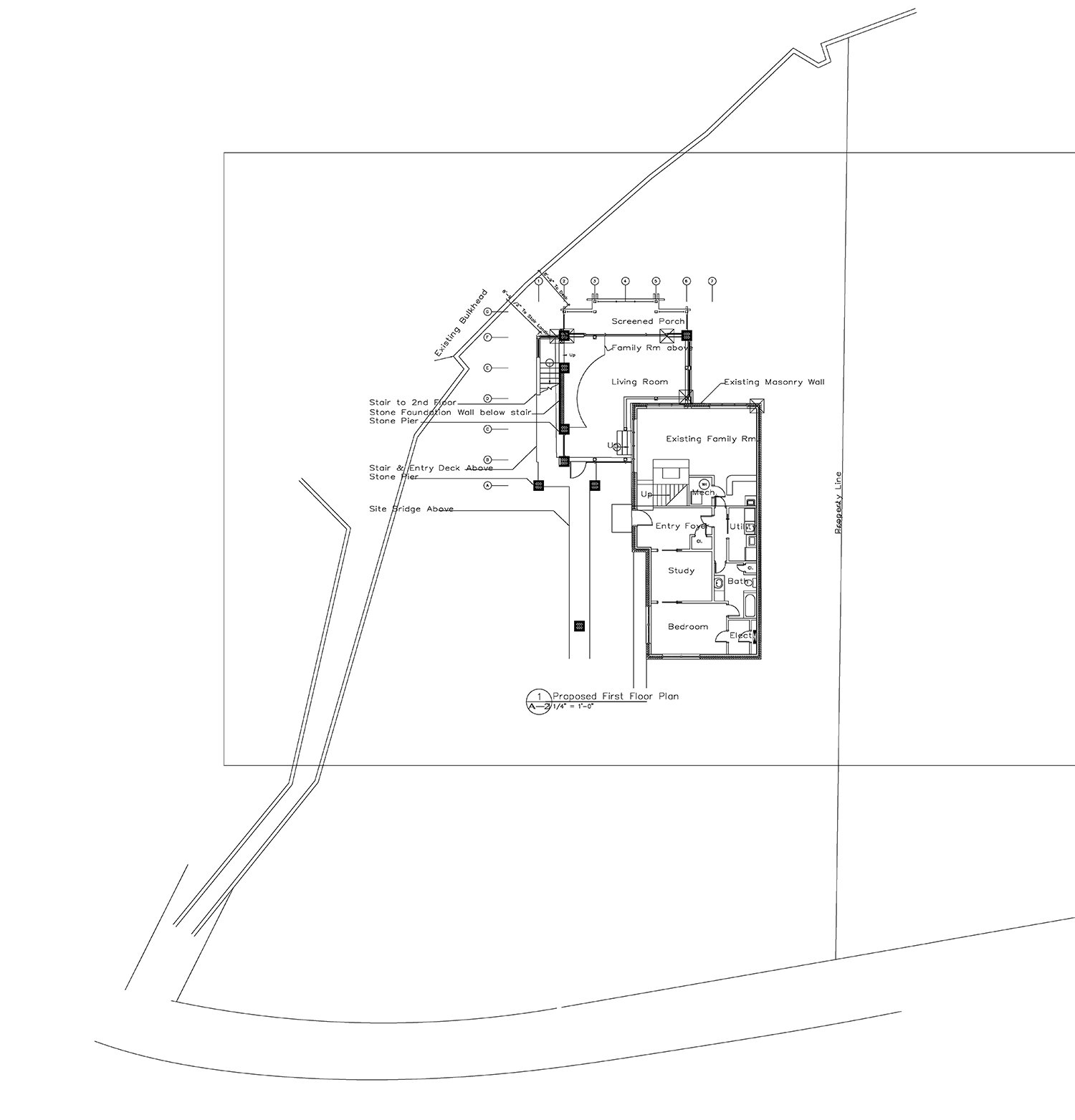

Existing house and lot—drawing by William E. Evans, ©2004

Figuring how to handle the triangular shape of the lot was as much the problem as deciding the program to include in an addition. I reached out to a Fairfax County zoning official I knew to get a reading on the property setbacks. How did they interpret a non-rectangular site such as this? To my surprise, she told me the long diagonal running lakeside was defined by zoning as a side setback, meaning I could get as close as 15 feet to the water.

What we wanted was an enlarged kitchen and dining area—and an improvement on the mansard attic space with three narrow dormer windows to make it a real an office. “Make it look like an architect has been there,” Harry Weese would preach to his disciples.

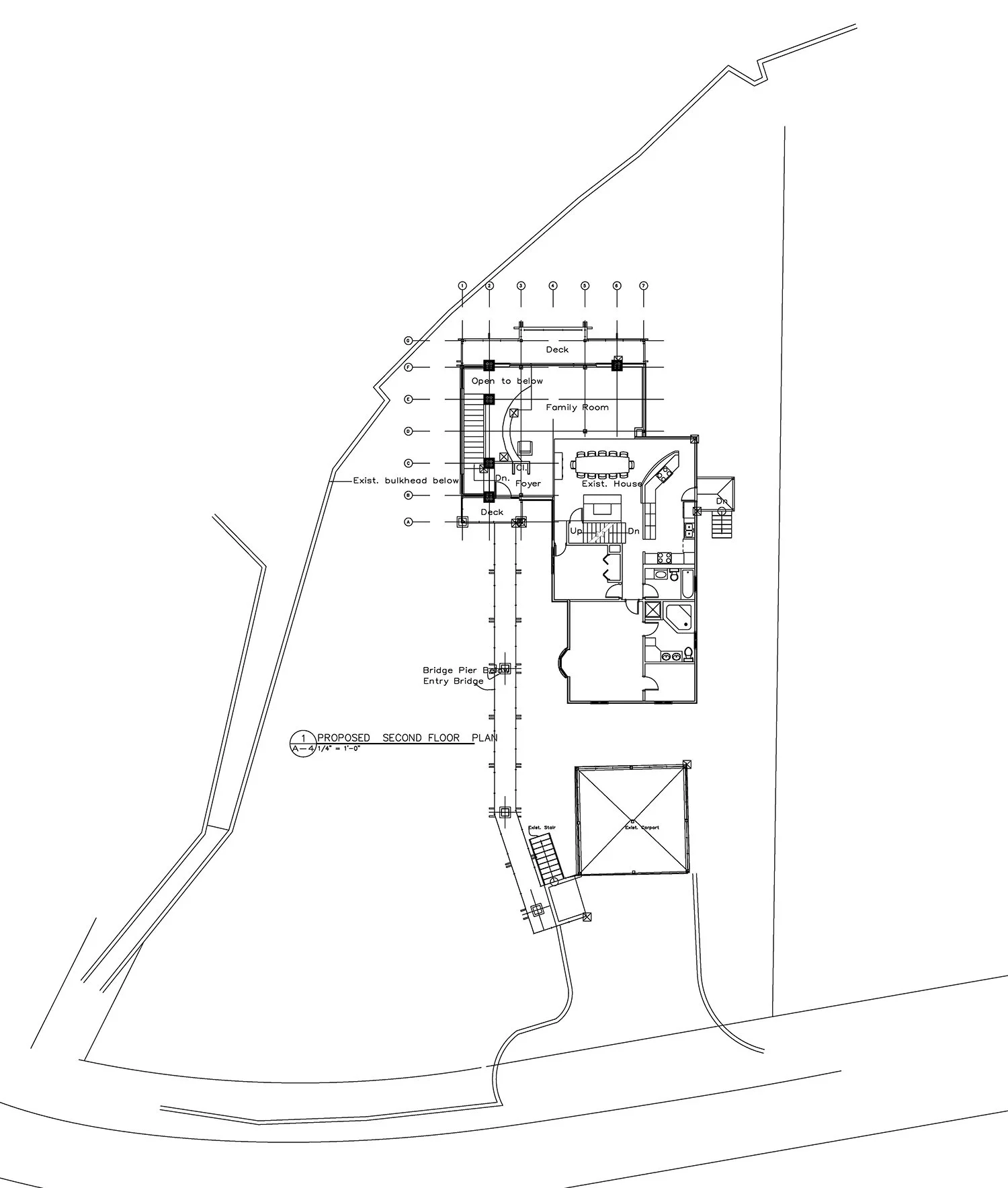

Simply slapping on a volume to the end of the existing house would kill any natural light coming into the kitchen, assuming we’d not move it forward. So from the start, I wanted to step to the side with the addition, leaving the original house with the view that it already had. The house needed all the light I could give it. From the beginning, it was clear we had two views in opposite directions, the main one toward the lake, but an interesting secondary view looking back across the side yard toward the road.

Early, it occurred to me if the living room was relocated to the ground level, it would bring us closer still to the water—leaving lots of room above for a formal dining area and expanded kitchen. I was also fooling around with the attic, replacing it with a full-blown office and outdoor deck. If I wrapped the new living room around the existing downstairs family room, it would create a room within a room for music and small conversations. The family room was (and still is) a narrow space between the exposed brick exterior wall with windows on two sides and a massive fireplace on the opposite wall. The windows would be replaced in the early schemes by openings into the living room, with the latter set a few feet lower.

It was coming together incrementally, like the pyramids.

Proposed ground floor plan—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Proposed second floor plan—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Proposed mansard floor plan—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Architectural Desktop

The then-current Autodesk program, Architectural Desktop (ADT) had been introduced a year or two before. I used it at the office, so I would drive to Shirlington on the weekend to use it for my own design. ADT was Autodesk’s first attempt at 3D modeling. Not the most elegant software Autodesk ever released, and buggy as hell with lots of unexplained blue screens of death, but offered it with a 3D Max program to sweeten the deal. One could never tell if it was the NT operating system or the software; flip a coin.

Shortly after, Autodesk—seeing the light—acquired a startup company’s product named Revit—too late for my house project and several libraries the firm lost money designing. My partner Dave kept quiettly saying ‘look at Revit’ but I was stubborn. Dave was right: ADT absorbed too many cycles, more brain cells than the tequila—and didn’t much thrill my loving companion, when I’d grab every free hour to wrestle with it.

You might notice how I was going crazy dreaming, spending time I couldn’t get back, rueful only in taking so long. Until we received that first cost estimate.

Aerial of proposed house minus context—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Option 5 entrance—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Lakeside elevation—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Lakeside perspective—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Lakeside perspective—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Ground floor perspective—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Entrance foyer—image by William E. Evans, ©2004

Bridge

Did it make sense? Even avoiding the trees, a bridge was clearly going to be an intrusion on the yard, but if the front door were ever to be improved, how else? Simple logic said coming to a front door shouldn’t involve fifteen feet of vertical grade. Besides, the suggestion of a dock leading one toward the water seemed a sweet nautical metaphor—hopefully an improvement on blue and white wallpaper.

So we received our first cost estimate. All told, it was more house and more of a mortgage than we felt reasonable, so it was back to the drawing board. In the end, that first experiment took something like three years. The entire project would take eight years, from start to finish. And the hot tub deck on the upper level would have to go before we were finished.

And several years later, when I submitted the final design for a building permit, the zoning folks objected to the bridge running across the side yard they claimed was actually our front yard, ‘You can’t do that!’ My riposte was ADA made me do it—true that. Score one for the architect.